Yulia Ivanova

Exams. Joanna's Page 19

And his face with closed eyelids turning to the window and mysteriously whitening in the darkness.

Later it began to dawn, and his face changed at every moment of the dawn, and this was a miracle she couldn't get rid of, though she was afraid to death that Peacock could wake up. She watched him through her eyelashes, and it seemed that both of them were somewhere deeply under water.

Yana knew that she would fall into deep sleep, and when she woke up, Peacock would disappear without a trace as a miracle, and the camp bed would stand at his former place at the storeroom, as if there were no Peacock here. And there would start long days of waiting for a message or a call, days of voluntary duties at the editorial office, when she couldn't do anything right and gasped at every phone call. And the worst thing would be her loneliness and full impossibility to confess this obsession or illness by the name of Peacock to somebody.

He is a fop, a dandy and a stranger.

And for some reason she wasn't able to pick up the receiver and dial his number: not only the receiver of the editorial staff but also later in Moscow where she would go to take winter exams no idea flashed across her mind to drop in any public telephone and solve all her problems per two kopecks.

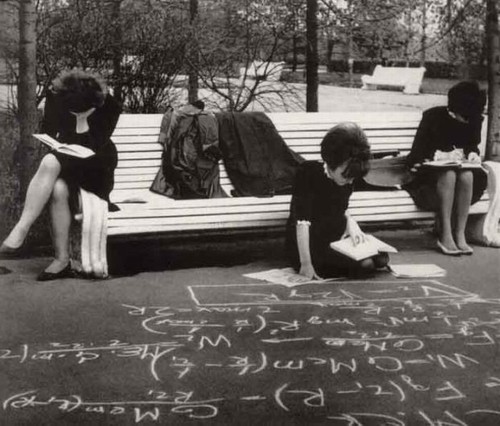

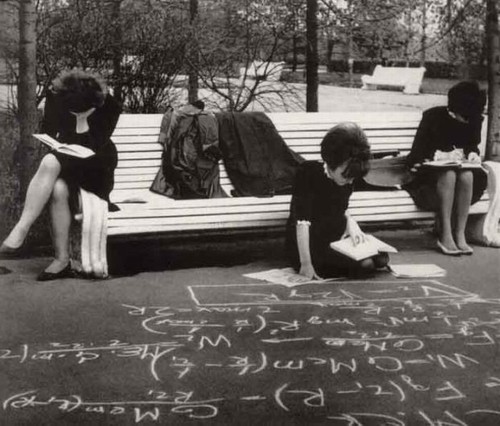

Being surrounded by books she would be sitting in the university library together with other martyrs-correspondence students, and two-week great pressure from the side of teachers would almost heal her from her obsession.

She would have got new friends from the entire Soviet Union. They would jointly attack examiners, blackmail them, cry, think up the most incredible sentimental and romantic stories, use exquisite diplomacy which would be envied even by Talleyrand and the most crafty accessories for hints and cribs: pockets under skirts, thighs with written dates and events on them, and all of that was done for getting good marks in student's record books. All of that would look like a merry and risky game with a little part of seriousness and thrill for forty-years-old boys and girls.

An especial joy for her would be heir short two-week friendship and solidarity, remarkable by its shortness, and feeling that their childish-adult game which consolidated them was about to finish. They would again become literary workers, special correspondents, proofreaders, fathers and mothers and some of them even grandfathers and move to their separate homes, to their everyday life until next exams.

And after next exams they would carry out feasts, journalistic stories and discussions with all advantages of their adult life and experience that would make those improvised meetings even more precious than ordinary students' seminars.

Evenings she walked with eccentric and reliable Roma from the medical faculty from the library to Paveletskaya-street where she would overnight at her mother's lady friend. He would carry a heavy string bag with books she would ask for night at a librarian. Tears would flow from their eyes because of icy wind on the Kamenny Most. "Go behind me then it won't blow cold on you." With this string bag Roma looked like a solicitous father of a family with his dark-colored old-fashioned coat and shuffling a little clubfooted step.

For a moment she would be struck by her memories of Peacock and his truly cowboy's tread, with which he amazingly imitated the American actor Yul Brynner as she would understand later, and his dandy's jeans and parti-colored plumage fitting him like a skin of poisonous snake.

They would go though Kuznetsky Most and Pyatnitskaya-street and then along tram railway. They would have launches not at the students' dining hall but at a cafe in Gorkovskaya-street. It would be very wasteful for students' pockets, and Roma would have to save money. She would understand it later and feel shame because in comparison with Roma she was a millionaire - she got her monthly wages and honorariums in addition.

"A tram is coming. Let's get on.''

"I have been sitting for the whole day. The Japanese say one must walk 10 thousands steps a day.''

""It's easy for them to say so; it's warm there.''

"You are frozen, let's run. Why do you say that you are a rated athlete?

"Give me a handicap - the fifteen kilogram's string bag. Make a start!"

They ran along tram railways, along a frosty street; occasional frightened passers-by dashed aside and drew close to fences. At a brick house they said good-bye to each other because they were in for a night of rite-learning. Their refreshed brains now were able to contain all books in the string bag.

Once Roma called her to a skating-rink. Yana could skate not very well, and her rent boots were too big for her. Limping as far as a bench Yana thought what was better: limping back to the wardrobe or dragging there in woolen socks without boots.

And then Roma somewhere got a white tape, tightly laced up her second-hand boots, and they started going round. In his strong arms nothing bad could happen, and Yana believed that she can't fall and break her nose, that she was invulnerable and immortal like Antaeus on the earth.

She experienced something similar only in her early childhood at her father's arms. They rush along outrunning everybody. Swish, swish! They pass somebody's backs, scarves, jerseys and frightened faces. And she didn't care about Peacock and thought of him anymore. She only thought that she didn't think of him at all.

Once after one more exam when they hurried to the caf? they saw a passer-by falling to the ground. Yana heard cries, 'Call a doctor, call a doctor!" and saw that Roman disappeared and not at once understood that he was a doctor, and the crowd surrounded him. She looked for him by her eyes and recognized his voice.

"Let everybody come back. Fresh air is needed!"

The crowd made way; she went through it and saw Roman without his coat and jacket. He stood on his knees over a lifeless body of a man spread strait on snowy medley of a side-walk. Roman's arms with rolled up sleeves penetrated into the body rhythmically and very deeply.

"Come back, don't hinder," Roman roared at the crowd and shot his angry and invisible look at it. She saw drops of sweat on his forehead, and again his fists penetrated into the man's breast. She heard a crunch and with horror understood that it was a crunch of the man's ribs. She thought that she needed to pick up Roma's coat that lay in the snow - all of that happened within a few minutes. Somebody pushed her away and the crowd closed up. Then she heard a wail of an ambulance and saw hospital attendants with a stretcher.

Somebody helped Roma on with his coat, and Yana didn't understand at once that his searching look has to do with her.

"OK, let's go."

A man caught up with them, "Doctor, what is here? When I press this place it hurts.

Excited crowd in the foyer of the cinema poured from the buffet into the hall (they come to the show in time). In the dark hall he got cramps in his hands and people started spiteful hissing, "Hush, don't hinder."

They showed 'The Waterloo Bridge.

A few days later she would go home and find out that shooting the film were in full swing and that Peacock had time to show himself in all his beauty, "all his colleagues were blockheads and botchers and only he was a genius; even his own picture crew can hardly bear him; would you hear how he shouts at the cameraman and doesn't pay travel allowance to lighters, wasting their money with a braided gal who comes to him from Moscow."

All of that was told to Yana at the editorial office. She gasped and horrified and then told as colorfully as possible about Moscow, exams, new interesting friends, kebab house caf? and about Roma, claiming that their relations had been serious and finding bitter sweetness in her 'revelations', in her public denial from Peacock, in scorn towards herself for an unworthy womanly play by which he intended to return former favor of her colleagues staff towards her.

And later she made herself go by the shooting area where Peacock tormented pale and haggard Vsevolod shouting both at him and at cameraman Leonid who was unbuttoned and had suspiciously shining eyes and our photojournalist George who was also a little tipsy ran around, enjoying all that cinema disorder.

And a fateful girl in a sheepskin coat, without a cap and with braided hair powdered with snow, with penciled eyelids and with thick Negro lips in lipstick of almost inky color - this embodiment of ominous and vicious beauty was sitting beside Peacock, showing her knee through a slit of her skirt and giving him steaming coffee from a thermos.

Yana stopped only for a moment to inhale the smell of coffee and perfume of the fateful girl and the smell of imported Peacock's cigarettes. Yana didn't know yet that in this estrangement in time of work they are very much alike.

She hurriedly went away. A bitter lump swelled and tore her throat. It seemed that when she made even the slightest move, tears would flow from her eyes nose, ears and every cell of wooden Yana's face. She cried so in her childhood because of inaccessibility of the world.

But now she couldn't cry; she must carry her wooden face past Peacock with his suite, past passers-by, past houses and trees and past old-women chattering on the bench by their 'Big House' to the brown rectangle of the door with rhombuses, to dark nothing up the squeaking stair.

Yana carries herself like a bowl with precious poison, so bitter and so sweet one.

Home page