High Soviet Life. Joanna's Page 31

Yulia Ivanova

High Soviet Life. Joanna's Page 31

And the more one succeeds to dig out a black abyss, the deeper it is in him.

And life was in full swing. After graduating from the university Yana unexpectedly won a creative competition and studied at the University Scenic Courses for two years. In the beginning of the sixties she studied in the House of Cinema and several times a day viewed masterpieces of world and national cinema. She listened to lectures of Romm, Shklovsky and Landau. On the opposite side there were the Writers' House and a beautiful kitchen, in both houses there were seven spots of cognac. There were creative workshops in Bolshevo and Repin, young and budding literary and cinema elite from all over the Soviet Union. Later they became not only masters of word and screen but cream of the future of 'perestroika', democrats and nationalists.

But then no perestroika was dreamed of; there was a thaw, although it was freezing already but not very much. High Soviet life boiled and Cinderella Yana, being surrounded by an elitist environment, was accepting new pieces of information, names, manners and tastes.

The first shock from 'real serious cinema' soon passed. The more real and serious a film was, the more manifest was a sense of some kind of substitution and fraud, which caused even worse thirst. She ran away from screen psycho-killers, blood, sex, and became neither a professional, nor a lover of cinema, sharing healthy tastes of boys from the south who preferred westerns, comedies and roar of dice in a cup under their palms.

Once Mikhail Borisovich who was director of courses and a former intelligence officer found them doing these shameful things:

"Oh, my God, why was I taking on all this trouble, why have I subscribed to masterpieces and raised funds. What can be expected of these savages? But how dared you do so, Yana!"

He was really deadly hurt, and then Yana saved everyone. She approached him trembling with indignation and kissed his cold an old man's cheek:

- We won't do that anymore, Mikhail Borisovich.

And with amazement she understood that this elegant and refined white-haired gentleman who went through fire and water was a child. She watched him calming down and could see only a touching child. And she was ready to cry with shame.

"Go to the hall, right now," he mumbled disappearing in a rectangle of an attic door.

Southerners went downstairs like a herd, and Jana, carefully followed them on her hated 'heels' In the House of Cinema they had to follow fashion. She tried to understand why the analogy with a 'helpless child' touched her so much. Her Philip was an ordinary child, but as a mother she never felt this disarmingly pathetic helplessness. It was a small all-powerful despot who always knew what he wanted. He was a cunning schemer, skillfully playing off with her mother and grandmother.

Nevertheless, her life sometimes didn't succeed. After unexpected turning of a key by an unknown hand a Roulette stopped in a sudden silence; her heart ached sweetly and anxiously and her eyes became wet, though it used to be difficult to make her cry.

In such times she was indifferent to the Gioconda's smile.

She discovered with astonishment that as well as these Papuans from the 'dog world' who were creating models of planes hoping that steel birds would come down to them, she kept waiting for a miracle, being deeply convinced in her heartstrings that it would happen without fail.

She did not know what kind a miracle it would be; it just attracted her by a white kite, a white letter from her father and a white seal, as it was in her childish dream. It was a flight in the golden-blue light in stopped time.

It was strange but she still knew by her secret knowledge that the most important works, daily and long-term ones, were not so important; it was this expectation which was important and which was Yana herself, but not the things which Yana was saying and doing.

And once she realized that everything was bad, then everything was well, it was only necessary.

This was endless 'necessary'. It was necessary to send Philip and her mother in law to Evpatoria; it was necessary to place him in a special school; it was necessary to get a voucher to the house of creativity for Denis or for herself. It was necessary to get medicines and a sick-leave, and also visit some shops, workshops, studios and so on.

Philip was growing up; her mother in law was growing old. She and Denis also didn't become any younger. A secret war of self-esteem was raging among them. Again and again the defeated winner Joanna went to her desk, being advanced in years, cases and series. And their character, Paul Kolchugin who was a superman and an idol of youth, especially girls, would bury his killed fianc?es one after another because a married character was a vulgarity and nonsense.

He should have belonged to everyone, not belonging to everyone.

The deeper Joanna buried herself in criminal underworld, the more often was she criticized by her brothers in pen who said it was enough to toil for Gradov like a slave. As she wasn't able to earn all the money, it was time for her to take on true literature and write masterpieces because she was talented!

About this talent she would hear all her life. The mysterious source from the depths of her ego, which flew merrily, uncontrollably and generously, later dried and turned into a gloomy dark pool, whose depth frightened and enticed.

Sometimes she seemed to herself to be overflowed by this sinister darkness, powerfully aspiring to existence, and in fear rushed from her desk into a maelstrom of High Soviet life. The darkness seemed to dry up, but the dam of fuss was short-lived; the bitter poisonous potion again rose to the top and splashed over the edge.

The source was waterless or poisonous and not thirst-quenching - what was the difference? The water was undrinkable, and that was all. It was the only thing she knew very well.

That was what her talent was. She knew that she must not write the same mysterious deep knowledge, and only Denis could compel her to violate the taboo again and again.

Yes, she was his 'slave' and did not pretend to anything more. She hated that damned talent of hers, without which she would be able to live like everyone else: by her family, children, viewing parties, talks, resorts and travels abroad instead of feeling a dead dried up, raped and overflowed with poison.

She felt happy when her tooth, eye or head didn't hurt. When Philip was healthy and when Denis belonged to her. When a fridge was finally repaired when it was possible to get a windshield and forget about her typewriter. Just to put into its pouch and hide it into the wardrobe form Philip who, playing the war, knocked its keyboard, imitating a machine gun.

It was strange but it seemed that waiting for something was an authenticity or a reality. It was a vital process or a game that was sometimes poignant, sometimes charming and sometimes tiresome. She participated in it as if she were under anesthetic. Inwardly she felt dragged into a kind of empty and unworthy 'boring time'. But since this game was called life, everybody had to play it.

It was not her game and not her world; she no longer felt her rootedness in it. Now she was an alien or a stranger for everything and everybody. Moreover, other ways of life, of which surrounding people were dreaming and arguing and all kinds of western, democratic and consumer's things made her feel bored even more.

Everything depended on the notorious 'Why?' Needs were not worth of being bending over backwards. She preferred Oblomov to Stolz and only regretted she had no Zachar.

She realized many things at once and long ago as far back as in her youth in the fifties. She realized that nothing was possible to understand here. History of Russia was a mystery to her; things happening around more closely resembled the theater of the absurd; dissidents made her feel bewildered. 'Didn't they realize that the world and such a society were irrational? And even if you cut off a dragon's head, a new one would immediately grow up.

Having been abroad at film festivals and on invitations (Dennis had many friends since the time when senior Gradov was in a foreign service), Yana instantly adapted everywhere. She easily imitated and accepted temperature of her environment, absorbing manners, gestures, tone of voice, starting to speak a foreign language next day after arrival and Dennis and her countrymen felt envy. She was taken for someone else but not for a Russian; she could live anywhere, everywhere, adapted, didn't take root, while remaining a stranger as well as she was at her own country.

But she didn't like to travel, acutely feeling mystical danger of movement in space and time.

Not being uprooted in everyday reality brings a sense of unreality or unreliability. Human lives and destinies seemed to be feeble and hung over an abyss by a thread; she always expected troubles from her life, in horror watching how they happened with others. The world was strange, hostile and dangerous; and inevitable suffering in it seemed to be senseless against the background of final one hundred percent mortality rate.

It was like a death row with inevitable execution for everyone in it. One could settle here, have fun and love peace, considering it as some absolute good.

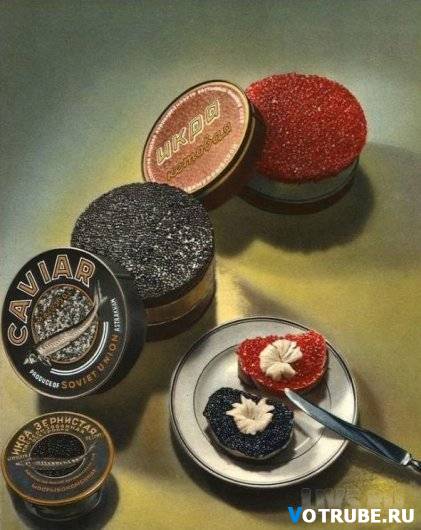

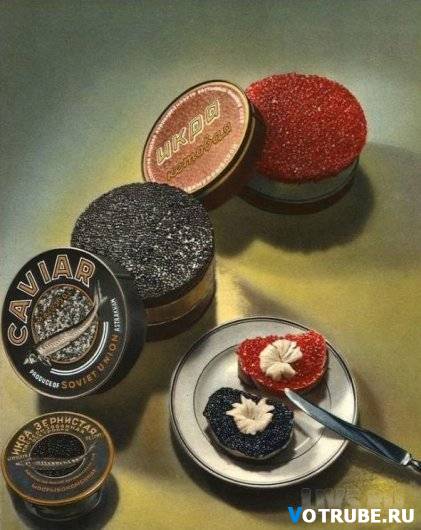

People especially succeeded in it abroad: a luxurious feast in the time of plague, selfless apocalyptic gourmandize, sophisticated methods of self-indulgence. Dishes for all tastes: from lobsters and a bare backside to all sorts of exquisite garnishes of music, steps, replicas, frames, lines, rhymes always caused in her mind a pitiful idea of universal madness.

Don't they hear constant clatter of carts? How do they manage to stifle it by those interminable carnivals, parades, fireworks and orchestras?

Or is it she who is mad and isn't able to really enjoy? In any earthly drink she feels deadly-bitter taste of poison. She is ill and insane. For her the world is punishment and imprisonment, cell with toys scattered around. Mechanically fingering them she tries to understand: 'Why?'

And only sometimes in the pile of colors, music, replicas, steps, frame and rhymes, beautiful and ugly ones, distracting, frightening and amusing toys there come across other words and sounds that are impossible as flowers in the snow. It is like shaking hands across the chasm and like a secret message from the outside: I remember and love, I'm waiting...

And her soul, as if it obeyed an unknown code, revived, responded by instant tears and by the same words, 'I remember and love, I'm waiting. This password wasn't learned by heart; it came not from her head, not even from her heart because she didn't have time for thinking and feeling.

She responded with unexpected. And Denis was irritated and puzzled when she, dragging him away from a prestigious movie or concert, suddenly stopped at the exit. 'Go, I'll be back in a moment. And that 'moment' lasted and lasted, and he, being dressed already, languished in a cloakroom with her coat, until she finally appeared with a strange smile and in mascara smeared around her eyes; she was never able to properly explain what had happened there.

He knew that now it was useless to carry her to visit, and he got into the driving seat and drove her home. And when he, as usual, imitated her stupor, trying to stir her up, she could play an unpredictable trick. She agreed to many things to get rid of him, ceding important won positions to him without a fight in the eternal war between them.

Home page